I wrote a paper for my senior project in college. This is that paper. It was finished around April 2018. I’m always learning and growing, but this essays explains a lot.

Today, I added even more to this lengthy essay. Maybe if I think about this essay, I’ll finally finish this particular project. Maybe I should just move on and work on other projects.

Indigenous futurism confirms life because colonial education kills. Colonial education, or the way schools and other institutions spread anti-Indigenous propaganda, can increase issues such as historical trauma, alienation, acculturation, discrimination, and community violence (SPRC). I was wary to talk about Indigenous futurism, especially for my senior project, since it is a heady topic. My senior project is a comic that takes place in the future.

I made this comic for people like me, urban Natives that needed hope growing up, even if that is only through representation in art. I made a webcomic out of a 38-page graphic novel that I uploaded on my website jellobillyocomics.com that I launched in my e-marketing class back in the fall of 2017 during Senior Project 1. There were three posters placed on the wall for my senior show that I made in advanced printmaking. The website and the business card were made with a similar aesthetic. I used screen printing techniques and mixed media with colored pencils, spray paint, comic markers and sharpies. The three posters are accompanied by thirteen framed pages from my graphic novel. From left to right, there is a twenty-two by thirty inch poster featuring two women on a motorcycle, a twenty-six by sixteen inch poster featuring a woman looking back at a robot, and then a thirty by twenty-two poster featuring a boy pulling his brother’s hair.

As a former graphic design major, expect graphic design influence in the posters I make in advanced printmaking. I hope for these posters to demonstrate craftsmanship and extensive knowledge of printmaking techniques. These posters are bigger in scale than the usual 8.5” x 11” prints I make. The posters are meant to build expectations and give the audience a chance to evaluate the comic itself. These posters are meant to show that comics, like movies, can be about more than super heroes.

The exhibition itself is meant to give off the atmosphere of a zine library. The beanbags, white wall, and black frames exemplify the humble setting of where somebody would share zines. There are hints of silver on the table and in the images on the wall to compliment the theme of robots.

Photo taken by Instagram @austinsively

This comic revolves around identity, purpose, and belonging. The comic itself is called Oak and Wendy. Oak and Wendy live in a future Northwestern Plateau area where the dams were destroyed, the rivers have salmon, and robots are on the loose, but suburbs no longer exist. I wanted to challenge myself with the story, character design, and media. I had already made several pages and attempted making a webcomic before, but this project is my first own personal website, made possible with Squarespace. The comic was created with ink and copic markers on paper. This is also my first published comic in color and by published, I mean self-published. I hope to prepare for Indigenous Comic Con in November, which will be at Isleta Casino. Indigenous Comic Con is a challenge to Indigenous erasure. I plan to add more backgrounds, details, and extra pages for the version of Oak and Wendy that will be distributed at Indigenous Comic Con.

The concept of family impacted me. I think the concept of family is not only sentimental, but also political. Capitalism and colonization have normalized nuclear families as the social kinship systems of America. This means that families are broken. The elderly are thrown away and we lose out on their wisdom and beautiful company. Isolation becomes more frequent. As an only child, I grew up romanticizing the dynamics of siblings. Siblings can go on adventures, build interpersonal skills, and argue. Wendy is a single mom that lives with her mother and two sons. I grew up knowing families like that.

By making my senior project through the posters, business card, and web comic in preparation for Indigenous Comic Con, I am showing that I am a professional comic artist that can finish projects and meet deadlines.I have been looking for different ways to challenge the paradigm and myself. The ability and scope of comics as a storytelling medium has not been fully explored, because there are negative stereotypes of comics being about superheroes and for children. The dominant culture has negative stereotypes of Native Americans being pitiful, voiceless, or dead. Positive Native representation through comics will fix the negative stereotypes. My project will be some of the positive Native representation we need. Of course, I am not universal in as a Native American, Colville, Yakama person, or comic artist. My comic will not be universal symbolism, but it will challenge the idea of a universal paradigm with its very existence. Indigenous erasure is unnecessary and will be vanquished. "Two or three centuries ago, Western philosophy postulated, explicitly or implicitly, the subject as the foundation, as the central core of knowledge, as that in which and on the freedom revealed itself and truth could blossom" (Foucault, "Power" 3). In other words, Western philosophy has often leaned towards individuals seeing themselves as universal and separate from communities and systems around them. With most writers and philosophers, we have to know their individual and cultural experiences to understand where they are coming from, otherwise there can be problematic misunderstandings.

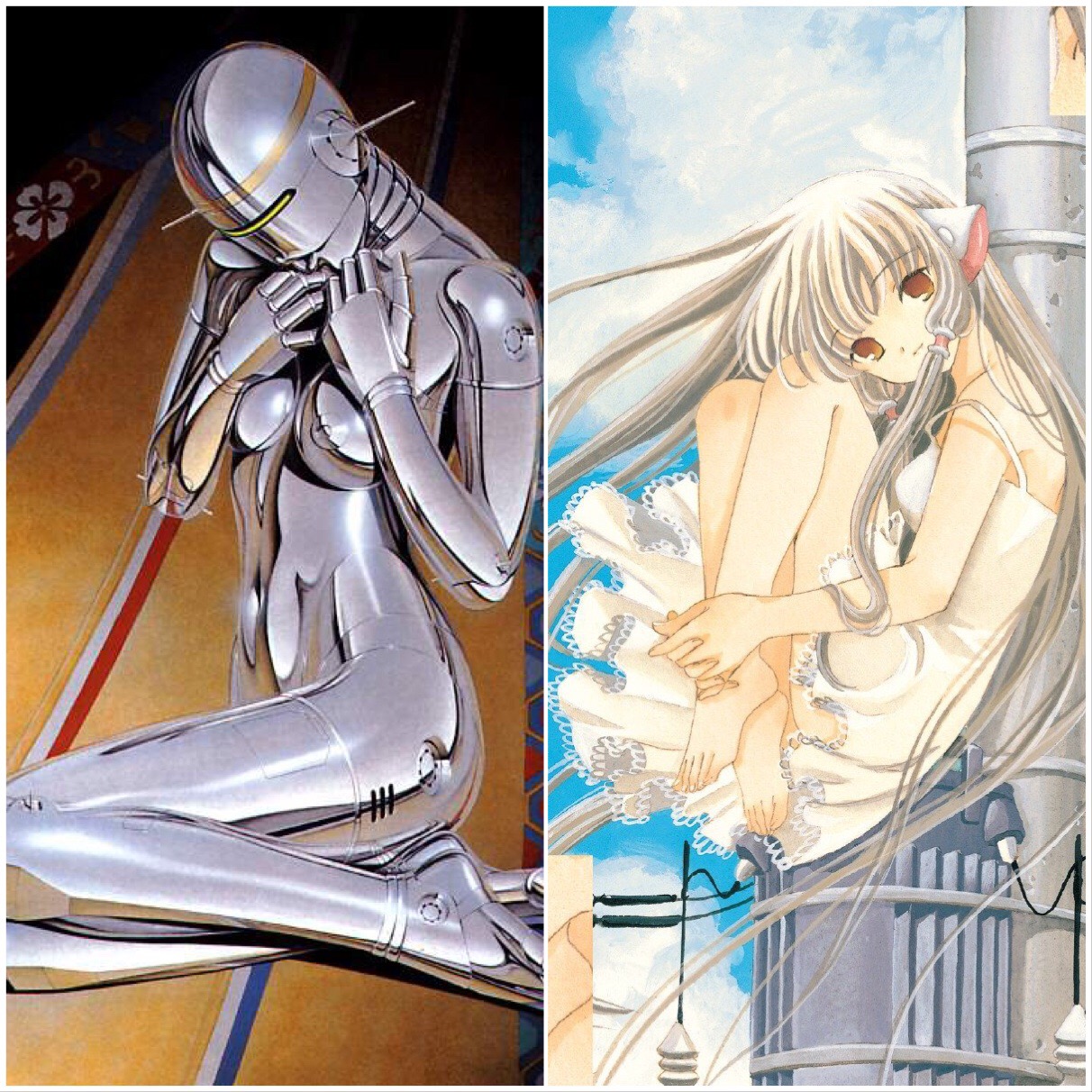

Research was needed for the posters and the technical aspects of this story, such as the references for posters, motorcycles, robots, postmodernism, Indigenous identity, science fiction, feminism, Coyote stories, and family dynamics. This comic is influenced by intersectional feminism and the desire to challenge euro-centric beauty standards. Unlearning euro-centric beauty standards is something that I struggle with. Struggling with beauty standards as an artist means more than feeling ugly, but also drawing different features as part of character design. My artistic influences are things I encounter in real life and stumble upon. Lately, I have really been into the philosophical historian Foucault’s work and his influence seeped into this comic. Foucault is so amazing to me that learning about him made me consider that I was too harsh on European thinkers. The artist team CLAMP’s comics have had a huge influence on my style, particularly the expressive eyes and pointy chins, but also the panel flow. The anatomy of American comics like spider-man and Deadpool have influenced me to step away from the "noodle people" style.

Another similarity I found between the French and Indigenous liberal studies was the contradiction to the idea of linear progression through change. As explained by Cornel West, the march of time is not the same thing as the march of truth. "The idea of knowledge as continuous and cumulative, which is such a central premise of Anglo-Saxon epistemology, is alien to the French way of thinking" (Hazareesingh 13). There is a classic French saying: "Tant pis pour lesfaits" So much worse for the facts (Hazareesingh 13). "French thought is notable for its constant interplay between the themes of order and imagination, or between the cold linearity of Descartes and the unbridled expansiveness of Rousseau" (Hazareesingh 17). I have read that in some Indigenous cultures, things happen in a spiral or cycles, instead of a linear progression.

Something I don’t see enough of is dialogue about science fiction from an Indigenous, feminist perspective. While I’m not a universal Native American or universal for all women, I will attempt to contribute to the list of Native and feminist writers that are interested in science fiction and the symbolism behind cyborgs, androids, and robots. I am planning to finish a graphic novel that involves androids and robots. I have really enjoyed comics for years and found that many comics in the United States have a connection to science fiction. For example, many people sell comics at science fiction conventions, while many people also sell science fiction at comic conventions. The two subjects tend to share an audience, but there are comics of a non-science fiction genre and there are science fictions outside of the comic medium.

There aren’t enough comics created by people that aren’t heterosexual white men. Major comic publishers Marvel and D.C. are both filled with heterosexual white male characters. Spider-Man, Superman, Batman, Wolverine, Cyclops, and Thor are all examples of leading, heterosexual white men. When there is a character that is not heterosexual, white, or male, that character is often a tokenized or the single representation of an institutionally marginalized group. For the D.C. comic Teen Titans, “Cyborg was the black hero in a comic that mistook tokenism for diversity” (SonofBaldwin). Researching the topic of cyborgs and androids has taught me that my representation of cyborg, android, or robotic characters can say a lot about my own views on race or gender and that I should try to avoid the racist, sexist, or ignorant stereotypes that other comic creators have made such as with the character Cyborg or Victor Stone.

“Victor Stone... was possessed of a great deal of self-pity, which seemed to be some sort of subtextual commentary on how white people feel about black people’s complaints regarding structural and social anti-black racism and white supremacy. Through Cyborg, the white gaze was able to position black people and our grievances against our circumstances as not only invalid and pitiful, but also as self-inflicted. It was always, to me, even reading these books as a teenager, a deeply problematic view of the plight of black people (it was white people, after all, who experimented on black people in this country)” (SonofBaldwin).

Phil Jimenez has discussed comic characters being a symbol for queerness through their status as outsiders, but it’s tough for me to accept only a symbol of queerness, instead of literally queer characters (FirstPerson). I am grateful that Phil Jimenez created queer characters and openly talks about it. Science fiction stories tend to have predictable tropes and symbolism because they were written by heterosexual white men. The symbolism behind cyborgs, androids, and robots in particular is filled with tropes that fit a heterosexual white male perspective. “Humanoid robots... have long been a stand-in for any exploited class of person. Even the word robot is derived from the Czech word for slave” (Penny). The symbolism and representation of cyborgs, androids, and robots is affected by race, gender, nationality, and more.

Nationality and war has had a complex impact on the representation and history of artificial intelligence and robotic technology around the world. “In the 1970’s and 1980’s there was great enthusiasm for artificial intelligence in academia and the corporate world” (Wilson, Information 787). There was optimism that “the simulation of human (or even superhuman) intelligence” would happen “within a few years” and the Defense Department Advanced Projects Research fund (DARPA) used to receive investments for large research sums from the U.S. government (Wilson, Information 787).

In Japan, science fiction was influenced by World War II and afterward in 1956 Gojira, or Godzilla, was created (Nowell-Smith 320). After the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, there was “the beginning of normalized relations and increased commerce between the United States and Japan” (Nowell-Smith 320). Japan had a radical change “from the victim of high technology to high-tech superpower” (Nowell-Smith 320). Japan’s boom in innovative technology with high-tech inventions, like the walkman and other entertainment, led to more science fiction representation such as Ghost in the Shell, a comic series where robots and cyberbrains exist. The Japanese comic series Chobits has made me think about the sexualization of feminine robots. Another feminine robot that comes to mind is the character Android 18 from DragonBallZ. When I was a kid it wasn’t weird that she was an android. I’m not Japanese, so my view is always going to be skewed in some American way. I think the line between objectification and being open with your sexuality is very blurry.

An interesting part of researching androids has been realizing that “andro”, the root for man, is seen as the default, gender-neutral root. When I realized that I had never heard anybody use “gyno”, the root for woman, in relation to humanoid robots, I was amazed that I had more internalized misogyny than I knew. When I did look up “gynoid”, sexualized robots, or “fembots”, appeared. Even saying “gynoid” out loud makes people think about vaginas, while saying “android” is seen as typical sci-fi talk. It made me think about how women are often sexualized, while men are seen as sex-neutral. An example of the sexualization of women can be seen in how women’s clothing is often sexualized and made for aesthetic, while men’s clothing is often made for practicality and comfort. The fact that men’s clothing has practical pockets, while women’s clothing has aesthetic pockets says a lot about the separation of gender roles. I struggle with whether to write “gynoid” or “android” when I want a gender-neutral term. The term humanoid doesn’t necessarily mean robotic. I tend to use android more because the name gynoid reminds me of vaginas, and because I associate the term gynoid with porn.

After I saw Ex-Machina in theaters, I was influenced to think about robots and gender more. It felt fresh and interesting compared to other movies that were coming out, but the ending left me bereft. It felt like the android woman was a symbol for the male heterosexuality of the human characters. The android manages to escape the male characters, but the movie ends after she’s escaped. I was interested in what her life would be like after she finally got away. The fact that the movie ended after she escaped the men made it feel like the mens’ narrative was more important than her narrative. “Every iteration of the boy-meets-bot love story is also a horror story” because the concept that “for the fembots, the men who own them are obstacles to be overcome, with violence if necessary” is supposed to be universally scary for all audiences regardless of gender (Penny). The implication that men are universal humans can lead to internalized misogyny for women in the audience. The narrative of escaping fembots as horror is a part of the male writer’s fear of women’s liberation.

Escapism is a part of duality. An interesting aspect of escaping characters is the fact that fiction is often a form of escape from reality for the audience. We are often taught to think of a happy fantasy as the alternative to a sad reality. DC and Marvel Comics artist and writer, Phil Jimenez explained, “I feel like I grew up creating fantasies in my head all because of the sense of difference” (FirstPerson). Sometimes, escapism as a happy fantasy can ruin our chances of imagining ways to make our own happy realities. For me, it’s been tough to imagine happy endings sometimes. There’s an implication that survivors of abuse or oppression shouldn’t imagine themselves happy when they’re constantly cut off from seeing happy endings in fiction, especially when queer characters, female characters, and characters of color are often killed off in fiction. If every action starts with a thought, then the scope of fiction can be connected to our scope of thought. After all, many inventions in science fiction have become reality.

Not only do women need positive representation through science fiction, but Indigenous people do too. Positive representation increases empathy for other people and lack of empathy has a connection to violence. We need Indigenous characters to show that we can imagine ourselves in the future. Science fiction as a genre can be explored and redefined in amazing ways when we test cultural boundaries in narrative. “Science cannot proceed successfully for long without the broad interest and support of the culture at large” (Wilson, Art+Science 200). It makes no sense for a “techno-cultural society” to separate technology from the humanities (Wilson, Art+Science 200). An example of Western art normalizing the separation of science from the humanities is in the iconic film Metropolis when the only human woman character says, “there can be no understanding between the hand and the brain unless the heart acts as mediator”. If representation is a vital part of the humanities and the humanities are what keeps science ethical, it follows that positive representation is necessary in science fiction.

Comics can be a way to cope and a way to heal, but also a medium for representation. My thoughts on the definition of art have changed while attending the Institute of American Indian Arts. On the topic of defining art, “the question has engaged many because creativity is seen as the quintessence of being human and a good test for AI concepts and procedures” (Wilson, Information 789). I used to not think about the racial, ethnic, or gender identity of any of my comic characters. Then I wanted to make comics that were socially aware. Lately, I want to make comics that go beyond representation and diversity. There seems to be a dichotomy between using art for positive representation and as a way to heal. Sometimes, I wonder why can’t art have multiple motivations? There are some artists that see expressive art as selfish and not a real contribution to the community, while there are other artists that see representational art as conforming to the current system of oppression.

There are various Indigenous and Western definitions of art. The marginalization of Indigenous writers in academia and discussions of artificial intelligence has warped the dominant culture’s perception of human nature. When Western writers say things like “human artists always have rather selfish goals that usually involve money, fame, and sex. Machines are... better... to create objects of serene beauty”, I notice that they think Western values are human nature (Wilson, Information 791). When reading a book claim that “the increasing presence of computing power in everyday objects will continue to raise questions about the extend to which artist might be involved in designing... of such objects in the future”, I notice that Western writers make the increase of industrialized technology seem inevitable (Wilson,Art+Science 111). If I’m writing about artificial intelligence and robots, am I making industrialized technology seem inevitable too? Can we have a decolonized future where robots exist? At times, I ponder if using a Western medium such as comics can be considered creating Indigenous art, even though I’m an Indigenous person because the medium itself is Western and I mostly use the English language for my characters’ dialogue. Being a Native American nerd is weird sometimes. I think growing up in a city and being an only child really made me into the nerd I am, but I worry that being a comic nerd is too Western. These questions and worries about being a Native nerd aren’t that bad though, because if I keep wondering I’m bound to find some more answers eventually. It’s when I think that the ultimate, final answer exists that I get anxious.

I think stories are a big part of being alive. Stories and sequential images are shared all over the world, but the interpretation and use of symbols through stories and images varies. My definition of comics is basically a medium where stories are expressed through sequential images. For many contemporary artists, the meaning of symbols is an individual abstraction (Leuthold 195). For many Indigenous artists, symbols have cultural and sacred meanings. This difference in the meaning of symbols connects to the ethical treatment towards Indigenous aesthetics. A consequence of no ethical treatment or respect in regards to Indigenous aesthetics is cultural appropriation. I believe positive representation does increase the audience’s empathy for the characters, but at the same time, any good story will always be more than just representation. I don’t make comics specifically for a white or male audience, but I’m not against white people or men reading my comics. It’s a relief to know that my stories will never be universal.

In conclusion, doing research of symbolism involving androids, cyborgs, and robots to create a graphic novel that includes Native American women and androids is stressful, but in a good way. The concept of Native American science fiction is an anomaly in itself because it is subversive to say that Native Americans are the future. There’s a list of things that I need to keep myself aware as I write this story. I have to avoid the patriarchal narrative that imagines women being replaced with robot humanoids that will overthrow mankind. I am acknowledging that American comic publishers Marvel and DC have a long history of centering white men. I’ve learned that DC’s tokenized character Cyborg has connections to anti-blackness and hyper-sexualized racism. It’s clear to me that queer identity has connections to comics through symbolism of the character that feels like an outsider. I would argue that Native Americans are often given an outsider status through colonialism and that is my connection to American comics. Nationality and war have influenced Japan’s science fiction in a specific way. Gynoid is a sexualized term when android isn’t because women are sexualized in a dehumanizing way.

Other aspects to consider for science fiction are escapism and invention through fantasy. Then there is the question whether art can be both representation and a method for healing. I had to consider Western and Indigenous definitions of art and what that means for my comics. My decisions and theories will influence my future and possibly the future of science fiction.

Works Cited

Attebery, Brian. Decoding Gender in Science Fiction. New York: Routledge, 2002. Print.

Beavert, Virginia, and Deward E. Walker. The Way It Was: Anaku Iwacha : Yakima Legends. Yakima, Wash.: Franklin Press, 1974. Print.

Foucault, Michel, and James D. Faubion. Power. , 2000. Print.

Hazareesingh, Sudhir. How the French Think: An Affectionate Portrait of Intellectual People. New York: Basic Books, 2015. Print.

Leuthold, Steven. Indigenous Aesthetics: Native Art, Media, and Identity. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1998. Print.

Macdonald, Andrew, Gina Macdonald, an MaryAnn Sheridan. Shape-shifting: Images of Native Americans in Recent Popular Fiction. Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press, 2000. Print.

Martin, Diana, and Mary Cropper. Fresh Ideas in Letterhead & Business Card Design. Cincinnati, Ohio: North Light, 1993. Print.

McCloud, Scott. Understanding Comics: [the Invisible Art]. New York: HarperPerennial, 1994. Print.

Metropolis. Dir. Fritz Lang. Perf. Brigitte Helm, Alfred Abel, and Gustav Frohlich. Universum Film, Paramount, 1927. DVD.

Penny, Laurie. “Why Do We Give Robots Female Names? Because We Don’t Want To Consider Their Feelings.” New Statesman America. 22 April 2016. Web.

https://www.newstatesman.com/politics/feminism/2016/04/why-do-we-give-robots-female-names-because-we-dont-want-consider-their-

Sheyahshe, Michael A. Native Americans in Comic Books: A Critical Study. , 2008. Print.

SonofBaldwin. "Humanity Not Included: DC’s Cyborg and the Mechanization of the Black Body." Middlespaces. Wordpress, 31 Mar. 2015. Web.

https://themiddlespaces.com/2015/03/31/humanity-not-included/

SPRC: Suicide Prevention Resource Center. “Suicide Among Racial/Ethnic Populations in the U.S.: American Indians/Alaska Natives.” Fact Sheet/Issue Brief, Education Development Center, Inc., 2013. Web.

Wilson, Stephen. Information Arts: Intersections of Art, Science, and Technology. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 2002. Print.

Wilson, Stephen. Art + Science Now. London: Thames & Hudson, 2010. Print.